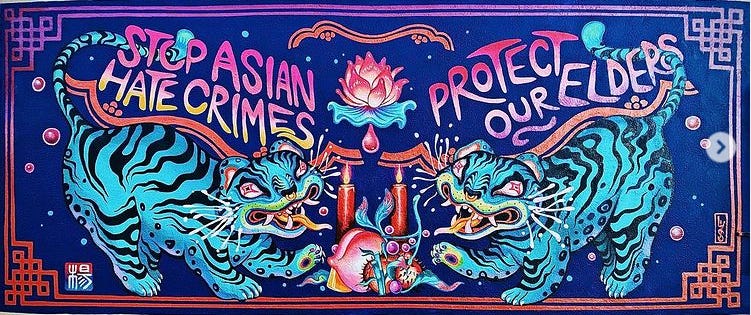

Mural by Lauren YS (@squidlicker on Instagram).

A tragedy, I will come to learn, isn’t confined to a single traumatic event. Sometimes, if one exercises the extent of their cruelty, a tragedy can also become its own long-casting shadow. Let’s take Antigone, for example. A civil war occurs offstage, before the play even begins. The tragedy, then, is created by the bureaucratic forces that have prevented Antigone from giving her dead rebel brother a proper burial. To add insult to injury is to know her other brother, the one who’d fought for the “right” side, is allowed his funerary rites. Injustice is arbitrary, Sophocles tells us, delivered by arbitrary rules. Let’s also not forget that Antigone, dear girl, is Oedipus’ daughter. The lineage of tragedy and trauma has known her blood for a long time, knotted into her very bones.

It’s been over a month since the mass shooting in Atlanta left eight women dead, six of them Asian American. But the reason why I’m writing this today, nearing the end of April, is because the tragedy hasn’t yet ended. Since then, the Asian American community has suffered innumerable and intolerable further wounds, mostly from white people: telling us that the killings weren’t racially motivated, that Asian Americans don’t face racism and oppression, that we’re “just fine” because Asian Americans on average earn more than whites. I have watched again and again as my Asian American peers refute each of these points with ample evidence on social media, again and again white people jump into the replies with arguments. From white people who think of themselves as well-meaning, tolerant, socially liberal people. Oh, the “good” ones, I’m sure. Trying to tell us what to think. Trying to instruct us on how to respond to violence against our bodies when they’ve never had to experience it themselves.

It has taken me a month to finish writing this because, frankly, I have not been okay. I have been grieving since last year, since Mike Brown, since Trayvon Martin, but this one — this singular tragedy has hit me like nothing else. Has stolen the soul from my body and refused to give it back. How do you grieve when grief is too narrow a word for intergenerational and transnational trauma, what is grief when what you feel is more like a survivor’s guilt? Of knowing your face or your mother’s or your grandmother’s face on someone else’s face; of knowing that you never could have been there, replaced that body, but on the one millionth chance that you would have — ?

These questions rattled my nightmares like unfed beasts. I have not slept well in a month. There have been nights where I have woken countless times but did not know why, only that my psyche had been disturbed. A grief that can’t be named.

And of course, insult to injury: the news cycle has since moved on, to other mass shootings, to other mass death, mercilessly crunching through our bodies for new and exciting content.

A Korean friend related what the community was feeling to the Korean concept of han, an inexpressible feeling of sorrow, melancholy, and most importantly, rage. I cannot borrow this word: I understand very deeply the weight of one’s generational trauma, and han is something that is uniquely owned by the Korean people. Instead, I offer up a word from my own mother tongue: língchí, the famed “death by a thousand cuts.” But in searching up the appropriate pinyin for this word, I discovered that this concept, too, has been used by Westerners to exoticize the Chinese people, and couldn’t even escape becoming the title of a Taylor Swift song. Han, I then remember, was also used for a pithy line in a West Wing episode. No matter where I turn, all of our cultural concepts have been pillaged and pilfered from, until even I can’t remember where I learned of língchí first — from my mother, or from some white writer trying to impress on me the savage ways of the Orient.

Why can’t you leave my people alone? This is the Asian American experience: being gaslit into thinking that your version of our story is the truth, being silenced or shamed when we yell, being worn down until we have no energy left to complain. One indignity after another until we bleed out on the slaughterhouse floor. Death by a thousand cuts.

So I have no energy left anymore for white people. You may think that’s harsh of me, but listen, I am a Libra, I have more patience than most. But white people have used up every ounce of it. Every single white person I have ever met does not understand that they possess implicit bias, meaning that it’s impossible for them to see their own racism unless they do some real deep soul-searching and can find the courage to admit that no matter how well-meaning, no matter how educated, their capacity for subconscious racism (and therefore real harm towards real people) is ever-present. But every white person is more afraid of doing the soul-searching, afraid of finding out that they might actually be a little bit more racist than they originally thought. So they look to people of color to assuage them, to tell them that they’re the “okay” white people, right? They’re not the ones we have to worry about, right?

If you’re white and you’re reading this, then let me assure you, I am always worried about you.

White people, you made up your stories about us and then created a whole system of fear and discrimination based on your own Orientalist fantasy. That’s not on me to fix, that’s on you. I cannot teach you how to dismantle white supremacy when it lives inside your head. Expecting people of color to clean up the mess you made is some real colonizer bullshit. So if you’re a white person and you only take one thing away from reading this, it’s that your love for human dignity — not just human life, but human dignity — must supersede your discomfort at your own racism. No one can do that work for you, except for you. And trust me, even if you think you’re exempt from this work, you’re not. Every single white person has to be engaged in a lifelong, continual effort to dismantle the white supremacy inside of them, otherwise you become complacent and slip back into it, because that’s just what being part of the dominant culture does to you. Don’t get angry with me for putting the long road of work ahead of you; if you really want to take this up with someone, I suggest going up a few branches in your family tree.

What I do have energy for, in the meantime, is investing in my own community and forging bonds with other communities of color. Over the next few weeks, because this essay exploded in length and scope, I’ll be taking a break from the regularly scheduled programming of RABBLEROUSE to explore the future of Asian American activism, what we can do to liberate ourselves, and other dreams of freedom. And just look — I managed to get my shit together in time for Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month.

If you are looking for an active way to help the Asian American community right now, several friends and I have created the Asian Defense Fund, a mutual aid group that is focused on providing free self-defense kits to vulnerable members of the Asian community. The sign-up form for reserving a kit is now live, so please, please send the link to anyone you think might need it. You can fill out the form on behalf of someone else (for example, Asian elders!) so please don’t feel like you have to pass it to exactly the right person. We just want people to feel safe walking outside right now.

Lastly, please note: throughout this essay, I have been intentional with language. I have not used the aggregate AAPI (Asian American and Pacific Islander) label to talk about the incidents of anti-Asian violence because I have taken the lead from Pasifika activists and thought leaders who pointed out that this current wave of violence is specifically targeted at the Asian American community, and I appreciate and value the care they put into pointing out this distinction. The aggregation and potential argument for disaggregation of the AAPI political group, and why it is a political group and not an identity marker, is something that I will most likely be exploring in the coming weeks.

The Elephant in the Room

So, I write this while knowing that this platform that I publish on has been harmful to the trans community. I won’t go into the specifics because both Emily VanDerWerff and Yanyi, two trans writers whom I respect and admire, have written very detailed summaries about the harm Substack has caused. (Please be aware, of course, that those stories may be triggering to you, especially Yanyi’s, which goes into more detail.)

I’m currently exploring other newsletter options, but in the meantime, I hope that because I don’t have any paid subscribers, that I’m not really contributing to Substack’s business at all. I’ll keep you all updated on the situation, but I wanted to address this issue and be transparent about the platform I’m writing on.

If you made it to the end, thank you for reading all the way through.