Every Unhappy Chinese Family is Unhappy in Exactly the Same Way

Or, the complexities of outness.

The essay below was originally published on March 22, 2022.

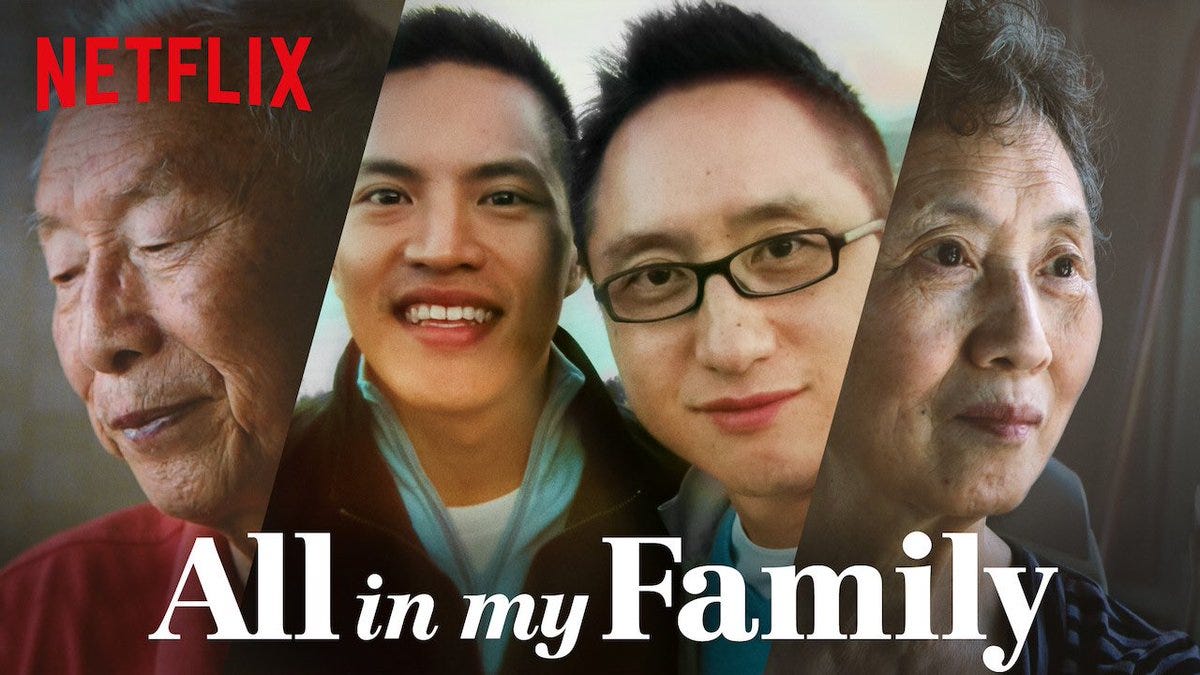

Yesterday I sat down to watch All In My Family for an otherwise unremarkable installment of Tongzhi Tuesday, my (extremely infrequent) column reviewing Asian and AAPI queer media. In it, filmmaker Hao Wu recounts his journey of coming out as gay to his Chinese parents, going through the surrogacy process, and trying to raise a family with his husband in the US all while fielding questions of, “When will you bring your wife to meet us?” from relatives back in China. The forty-minute documentary is short, sweet, and painfully honest. Most admirable is Wu’s willingness to show the harrowing ugly sides of these events, which makes the moments of tender, protective love all the more human.

Halfway through the film, Wu returns to China to visit family, and there is a particularly uncomfortable scene where he has to pretend in front of his grandparents that his husband Eric, with whom he has two children, is merely a close colleague. After they’ve left the relatives and are alone in some private space, Wu asks, “Eric, are you bothered by all this?” His husband gamely replies, “No. I think it’s all part of being in a family.” I don’t think he’s lying, either. Eric is Chinese American, so he understands this distinction — this little shadow play, these small unspoken tenets, the sly steps one takes in dancing around the truth and towards communal harmony, or something that looks like it, anyway.

It was all too familiar, the way Wu’s parents reacted to his life choices, and the things they said — he might as well have been recording video footage of my own family. While taking notes during the movie, I angrily scribbled in all caps: “WHY ARE CHINESE PARENTS ALL THE FUCKING SAME.” And the more I wrote this review, the more I realized that I could not separate my own experience from it. I was no unbiased spectator; all of my skin was in this game, and the review could no longer be only a review. Thoughts about my own queerness began to eclipse thoughts about the movie. And so, I wrote this instead.

A while ago, a Chinese American trans woman tweeted about her experience of going home to see her parents for the first time since transitioning. They sat at the dinner table together and shared a meal, but the parents couldn’t stop complaining. Couldn’t stop deadnaming and misgendering. A white queer suggested in the comments, if your parents can’t respect you for who you are, you should just cut them off. Which came off as paternalistically patronizing — as if a grown woman can’t perceive the kind of situation that she is in — and terribly, well, white. I wanted to grab my screen and yell into it, “CHINESE PEOPLE CAN’T JUST DO THAT, IT’S COMPLICATED!” When a culture insists so much on bloodline and ancestry, maybe it binds to you like a curse. And I don’t know a single Chinese family that doesn’t bicker and yell until everyone’s driven into a mad fury (in this respect Tolstoy was wrong — all unhappy Chinese families are all alike), so this is old hat to us, especially us queers. When we’re young, they hurt us. And when we’re older, we learn how the world hurt them to make them that way. I’m not saying that their treatment of us is right or excusable — part of every generation’s work is to undo the cycles of violence and abuse that preceded it — but we know, certainly more than most white people, what it means to coexist with imperfect humans. We know that life is difficult. You cannot sever pain cleanly from happiness. So sometimes experiencing harmony means having to experience some of the hurt too.

Even so, Wu settles on a position at the end of All In My Family that’s hard for me to personally swallow. Maybe it’s because I am much younger than him, maybe it’s because I don’t plan on having any kids, for the time being. But Wu, as a new father, says that he’s started to understand just how hard it is to raise children. Why his parents and older relatives were so controlling. And, most woundingly, how coming out had hurt his family.

There is this concept of “owing” in Chinese culture that’s never sat right with me. Because your parents gave life to you, gave you your body from theirs, you’re expected to carry out certain filial duties in return: care for your parents when they’re elderly, bear children to continue the bloodline, and maintain your family’s economic status, or else improve their station. When Wu comes out as gay to his family, his father seems to take it in stride, but it’s his mother who feels particularly slighted. You are my son, you are mine to have, you are my flesh and blood. What happened to the precious child that I knew? How could you do this to me? Children are viewed as an extension of their parents (and families at large), thus everything we do reflects back upon them. We can’t let anyone else know about this, Wu’s parents hastily discuss between themselves as they conjure up excuses for the “absence” of Wu's wife — the wife is dead! The wife is an illegal immigrant and can’t leave the US! The obfuscation is one thing; we can all lie by omission until our tongues are well and gone. The framing of being some inherent mistake, so shameful as to deserve a lightless, subterranean existence, is the thing I can’t forgive.

“A son of a Chinese family can never run away from his past,” Wu says earlier in the film, when he’s about to introduce his boyfriend to his mom and dad, “or at least not from his parents.” This line refers to the heavy burden on Chinese sons, who are traditionally prized (yes, I know it's sexist) more than daughters, as they are the ones who will inherit the surname, the property, etc. I have thankfully been spared the exact weight of this expectation due to a funny game of genetic lottery, but I am masculine-identifying enough that this line still hits me where it hurts. Truthfully, I had been perfectly content to stay closeted to my parents forever. It hadn’t been an issue at all, until I decided that I wanted to medically transition. And, unlike my sexuality, my changing body isn’t exactly something I can hide if I want to see them again.

You could say to me, well, then don’t see them again. But like I said, it’s complicated for us Chinese folks. Especially Chinese Americans. What kind of person would I be to abandon two elderly Asian people in a country that is not their own, surrounded by a half-alien language that will never come naturally when beckoned, not like it does for me, and at the apex of a pandemic and anti-Asian hate, at that. That’s not even lack of filial piety, that’s just called being an asshole. I say all this knowing that there’s a stark possibility that my parents, my mother specifically, may never extend me the same grace or humanity. Last night, I watched Wu’s mother say the same cutting, diminishing lines my own mother might use on me; he and I even share the same family name. I’m at the age where the lines of raw adolescent rage have faded and I want my parents to meet, for the first time, the totality of who I am — and yet, I know, this could all go terribly wrong.

I think it’s perfectly okay to stay in the closet of your childhood home. I also think it’s okay to come out and take those concessions that white people will never understand, to bear the brunt of those hits because your heart is big and wants to swell. But I never want anyone to think that coming out is an act that hurts anyone else. Earlier this year, I wrote in a letter to a friend:

The thing about changing too much is that people don’t take kindly to the change. They knew you as One Person, and once you don’t match the idea or image of what they have in their head, they feel betrayed. To them, you’re a body-snatcher wearing the face of their dear friend. They take it personally: “You killed them!” they’ll accuse,” you killed someone I loved!” The thing is, they’re not wrong. But you want desperately to correct them: Yes, yes, I killed them, but don’t you see? This new person is also me. That person you knew can also be and look like this; I exist across time as a multiplicity, as a continuum, not as a single word.

I change much too quickly and easily for most people’s comfort. I was recently talking to a friend I’d met in 2019, and I mentioned off-handedly that I don’t even recognize the person I was when we’d met. She replied with some shock, saying that her own personal evolution was nowhere as extreme. I realized then that my mutability is quite a unique attribute. And worrying to most. People like to define others; it’s why many react violently when you try to tell them that their categories are not real, or when you seek to defy and escape their constraints. It’s also why I feel so uncomfortable facing someone I haven’t seen in more than two years. I always end up wondering: who is it that you think I am right now? If I told you to vanish the old copy of me in your head, would you listen? Would you still love me, or would you damn me for stealing the face of a ghost?

Yes, fine, I want my parents to be happy, I want them to love me, I don’t want all their myriad sacrifices (and oh, don’t get me started on the sacrifices) to be in vain. But neither do I want to owe a blood debt that I never asked to pay. I want to be my own person, I want to be freed from that onerous burden of expectation, I don't want to be constrained. I want my dreams and desires to have some chance at living in this world, even if they never do take shape. You could say that this singular trait is what truly pegs me as American — this burning and unerring drive for individual sovereignty. But then again, I don’t think so. I think love of freedom is a universally human trait. There are plenty of queer people in Asia and across the world living under repression who don’t want to be hated or killed for who they are, who don’t want to suffer indignity at the hands of their own family members, who only want to be left alone and live in peace. None of us deserve to be punished for hurting no one.

I’m reminded of my favorite quote from the Hong Kong documentary Lost Course: “I was locked in Guangdong jail for twenty days,” says Hong, who had been arrested for participating in local protests against corrupt officials. “During those twenty days, I developed a view of life. I now believe that the most important thing is not health, but freedom.” For what is the point of being alive if you cannot exercise your vitality to the fullest extent of it? It just so happens that freedom is one of my favorite words in the Chinese language. 自由 is made up of the characters for “self” and “cause, reason.” Implying that one is ruled by one’s own determinations, in opposition to others’. Is that such a sin to want? I have to ask this with complete sincerity. Do we not all deserve the opportunity to derive our own reasons for existing in this mad, mad world? Do we not all deserve to be free in body and spirit?

All In My Family is currently streaming on Netflix.